Interdisciplinary Research Series in Ethnic, Gender and Class Relations

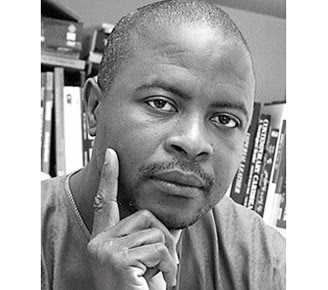

Series Editor: Biko Agozino, The University of the West Indies

Selected titles from thisseries

This series brings together research from a range of disciplines including criminology, cultural studies and applied social studies, focusing on experiences of ethnic, gender and class relations. In particular, the series examines the treatment of marginalized groups within the social systems for criminal justice, education, health, employment and welfare (for more information about the series: http://www.ashgate.com/ethnicgenderandclassrelations.

An Interview with the Series Editor, Biko Agozino

Series Editor: Biko Agozino, The University of the West Indies

Selected titles from thisseries

This series brings together research from a range of disciplines including criminology, cultural studies and applied social studies, focusing on experiences of ethnic, gender and class relations. In particular, the series examines the treatment of marginalized groups within the social systems for criminal justice, education, health, employment and welfare (for more information about the series: http://www.ashgate.com/ethnicgenderandclassrelations.

An Interview with the Series Editor, Biko Agozino

What encouraged you to enter academia?

I guess that it was the fact that in the village where I grew up, teachers were the middle class professionals that I had daily contact with and I admired them. My parents were peasant farmers and I laboured with them on the farms for meager returns. I made up my mind early that farming was not for me and focused my attention on book work with the aim of becoming a teacher. Whenever the teachers asked us what we would like to be when we grew up I always wrote about wanting to be a teacher and so it has been.

What made you (decide to) initiate this series?

It was a case of, ‘you can’t put a good book down’. I had my book proposal from my doctoral dissertation rejected again and again. One small progressive publisher appeared promising after the series editorial committee recommended my proposal for acceptance but the publisher rejected the recommendation on the ground that there was no market for a book on black women and the criminal justice system or else there would be a book on the topic already. Some logic. Then I came to Ashgate and two series editors turned the proposal down, claiming that it was too specialized to fit in. Fortunately, a young commissioning editor, Kate Hargreaves, went through the files and decided that she rather liked the proposal and if it would not fit into any existing series, then she would launch a new series with my book. And would I like to be the series editor, she asked. Wow, I was just happy to be getting my first book contract. To be asked to edit a series on the basis of that first book must be one of the highest honours out there in academia land. I jumped at the offer even though some senior colleagues warned me that it would be too much work for one individual and advised that I should recommend an editorial committee to the publishers. Over a decade later, I do not think that it is hard work, it is fun to work with Ashgate.

What are your academic background and research interests?

My first degree was a Bachelor of Science with First Class Honours in Sociology from the University of Calabar, Nigeria, 1985; my Master of Philosophy was in Criminology from the Law Faculty of the University of Cambridge, (Trinity Hall College), England, 1990; and my Doctor of Philosophy was in Law and Society from the Law Faculty of the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, 1995. My first tenured appointment was as Assistant Lecturer in the department of Sociology, University of Calabar, 1987-1989. My second tenured appointment was as a Lecturer/Senior Lecturer in Criminal Justice, Liverpool John Moores University 1994-1999 and the series started from there in 1997; then I relocated to Indiana University of Pennsylvania as Associate Professor of Criminology, 1999-2003; then to Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, the oldest historically black university in the US as Associate Professor of Social Relations, 2003-2006; and from there I relocated to the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago where I served as Professor of Sociology, Acting Head of Department of Behavioural Sciences, Coordinator of the Criminology Unit and Deputy Dean for Graduate Studies and Research, 2006-2009; and from August 2009 I will be relocating to Virginia Tech University as tenured Professor of Sociology and the Director of the Africana Studies Program.

Very briefly, where do you see your discipline going in the future?

I see my discipline (sociology) going more in the direction of critical scholarship, direct community engagement by public intellectuals and the increasing importance of interdisciplinary scholarship. All these could have been predicted from the focus of the Ashgate Publishers Interdisciplinary Research Series in Ethnic, Gender and Class Relations that I have had the privilege of editing from the start.

What has been the highlight of your academic career so far?

The highlight of my academic career so far is to hear my peers saying that my work has launched a new paradigm in my field, the decolonization paradigm. This is the sub-title of my first book with Ashgate that launched this series and a colleague who reviewed the book was the first to identify the originality of my emphasis on the decolonization model. Since then, I have elaborated on this theme (especially in my 2003 Pluto Press publication, Counter-Colonial Criminology: A Critique of Imperialist Reason which was hailed by a reviewer as launching a sub-field of Post-Colonial Criminology). More colleagues are proposing to write books on this theme and a course on Decolonization Criminology has actually been taught by a colleague in Canada. I am honoured by this positive affirmation of my work by colleagues internationally.

Whose achievements would you like to emulate within your own field?

That will have to be the great Stuart Hall. Here is a black man from Jamaica who has only a first degree in English but who transgressed disciplinary boundaries by becoming a Professor of Sociology and in the process helped to create a new discipline, Cultural Studies, while remaining a public intellectual, ever so critical and ever so committed to community engagement. Interestingly, while I was doing the field work for the book on Black Women and the Criminal Justice System, I heard Hall on the Open University television broadcast, deconstructing the poem, Tiger, by Blake and I was transfixed, watching this brother that I had not met but wished that I could meet. Low and behold, the very next morning, who do you think that I bumped into on Kilburn High Road? The great man himself, looking very ordinary and pedestrian. I started to holler as we used to do in Nigeria, Proooof! Prooof! He smiled and asked me what I was doing in London, he must have known from my theatrical accent that I was another Third World native like himself. I told him my research topic and he said, ‘that must be very challenging’. Exactly my own feeling even though some colleagues tried to discourage me on the ground that a man would find it difficult to do research on women. They would ask me to change my topic to black men or to corruption in Nigeria but my guru, Hall, saw where I was headed and he invited me to his home nearby to discuss my research. He asked if I had a pen to write his phone number and I said that I would remember it any day. He gave me the number and walked on and I rushed into the shop nearby to borrow a pen and write it down to be double sure. When I visited his cramped study with books everywhere. He asked me to explain my perspective and as soon as I started to talk about black women facing race, class and gender discrimination in the criminal justice system, he pounced and told me that I was talking about articulation. But, excuse me, from what I know, articulation is about the modes of production and all that. Yes, he said, but you can abstract it and apply it to social relations as well. He gave me a 1980 UNESCO book on race in which he has a chapter on race and class articulation and I have never looked back theoretically.

What book (not from the series, but generally) has most influenced your own work?

That will be The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon which we were made to read and re-read as undergraduate students when we took electives in Political Science with young radical lecturers like Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe. The book remains an inspiration to me that someone could come from the Third World, like myself, and make original contributions to knowledge that will last eternally.

What do you find particularly interesting about your role as series editor?

The most interesting thing is that it is close to being a cross between a genius and a genie. I make wishes come true for authors but not as a servant of the wishful writer since I can be a hard-task critic too. A colleague tells and retells a story of attending my author-meets-critics session at the American Society of Criminology. He approached me timidly afterwards to ask if I could comment on his book proposal before he sent it to publishers. I asked him what the book was about and when he told me, I invited him to submit it to Ashgate and told him that I would like to publish it for him in my Ashgate series. He could not believe that a series editor had that much power to grant wishes. Neither did I but working with Ashgate is empowering.

Any advice for people wanting to publish in your series?

Keep writing and never stop rewriting. Do not write one book and wait until it is published before you start the next one. At any point in time, make sure that you have at least ten projects at different levels of completion and as one gets published, start a new one to take its place. This is the recommendation of Charles Wright Mills in the appendix to The Sociological Imagination where he talked about scholarly craftsmanship. But specifically for my series (oh that sound great, my very own series), make sure that you reflect the wisdom of Stuart Hall by asking how your analysis could be deepened through race-class-gender articulation, disarticulation and re-articulation.

What was the last book you read?

Eric Williams and the Making of the Modern Caribbean by Colin Palmer. This was sent to me recently by Erica, the daughter of Williams, after I confessed that I had not read it and it is thrilling. The chapter on Eric Williams’ engagement with Africa is my favourite. But also interesting is the analysis of how discrimination was experienced within his family and in his schools where skin colour was privileged above contents of character but he escaped much of the discrimination because he had ‘good hair’ and, above all, because he displayed powerful intelligence. Before I read the book, I had visited the Eric Williams Memorial Collection where I discovered to my amazement that I have a lot in common with Dr Williams although I do not have his type of hair – his office desk is as messy as mine; I frown like he did by narrowing the gap between the eyebrows instead of lining the forehead by raising the eyebrows; when not smiling, my lips curl down slightly at the end just like his; I walk like him; I studied on scholarships and got first class honours degree like him; published my doctoral dissertation to critical acclaim a little like him; taught in a historically black college in America just as he did; and relocated to Trinidad and Tobago just as he did. Of course, I am no Eric Williams for there would never be another but I am proud to know that I have traits similar to his and of course he must have had traits that I do not have and may not want to have (tobacco abuse) and traits that he had that I would love to share (statesmanship); that is what makes each of us an individual.

Interview kindly received May 2009.